January 2023 Edition | Volume 77, Issue 1

Published since 1946

Poach & Pay 2.0: Understanding the Impacts of Illegal Wildlife Crime

The Boone and Crockett Club and Wildlife Management’s Poach & Pay Program recently completed analysis of early data from surveys of landowners, hunters, and conservation officers in an effort to understand the “Dark Figure” of poaching. Initial research under the Poach & Pay project in 2016 examined and reviewed state restitution systems for illegal take of big game species and found that the judicial systems were the primary obstacle for successfully convicting and punishing poachers. Phase II of the research got underway in late 2021 and results show that those interviewed consider the illegal take of big game to be a serious problem and suggest that more than half of wildlife crimes go unreported - even though the actual rate of unreported wildlife crime is likely significantly higher given the cryptic nature of poaching.

Fundamental to understanding the status and predicting future changes to wildlife populations is the concept of population modeling. At its most basic, a population model equation takes the current standing crop of a population, adds in supplemental animals from births and immigration, and subtracts animal losses due to deaths and emigration. The ability to accurately determine these factors can often make the difference between sound wildlife management decisions and those that may negatively impact the target populations or other populations that interact with them.

Of these four factors, immigration (movement into a population) and emigration (movement out of a population) are either negligible, offsetting, or estimated by tagging, telemetry, and movement studies. Determining the contribution from births is most often estimated by visual observations (cow/calf counts) or more recently, telemetry devices tied to the timing of birth (vaginal implant transmitters).

The last of these four factors, the death rate is the most difficult to measure or estimate correctly. Wild animals often live in remote places and are active at times when humans are not. The death of wild animals also happens under a variety of circumstances including predation, disease, accidents, drowning, fighting, legal hunting, and poaching (illegal take by humans). For many common game species in North America, legal, regulated hunting is often responsible for the highest percentage of their total annual mortality. Wildlife agencies use a variety of techniques to calculate the level of legal take including mandatory check stations, phone/internet check systems, and hunter surveys. These techniques allow us to accurately model the impacts of legal take on population levels.

The illegal take (poaching) of game species is arguably the most difficult of the population factors to estimate accurately. Wildlife populations can be estimated accurately even with significant levels of illegal take if the level of illegal take can be determined with some precision. However, even accurate estimates of illegal take have a negative impact on hunters by forcing the agencies to reduce legal harvest (via bag limits, season lengths, etc.) by lawful hunters. When we are unsure of our estimates of illegal take, the problem is exacerbated – for example, seasons and bag limits may be set too liberally, perhaps causing declines in the population.

In general, one of the greatest challenges to understanding and reducing crime is how to determine the number of criminal acts that go undetected by law enforcement. This undetected rate is described by criminologists as the “Dark Figure,” for person-on-person crimes and is influenced by many factors including personal injury, financial loss, fear, embarrassment, distrust of law enforcement, and locational or situational factors. These factors make calculating the Dark Figure a difficult proposition even for violent person-on-person crimes. Table 1 shows the Dark Figure estimates for crimes committed in the United States from Skogan (1973).

|

Table 1. Volume of Unreported Crime in the United States in 1973. |

||

| Crime | Total Incidents | Unreported (Dark Figure) |

| Auto Theft | 1,330,470 | 32% |

| Robbery | 950,770 | 51% |

| Burglary | 6,433,030 | 54% |

| Rape | 153,050 | 56% |

| Assault | 3,517,990 | 60% |

| Larceny | 22,176,370 | 80% |

| Total | 34,561,680 | 72% |

These rates of unreported crimes are influenced by a variety of factors. For example, crimes involving significant personal property loss (Auto theft) have the highest reporting rates, whereas crimes that may cause embarrassment or fear (Rape, Assault) have much lower reporting requirements. Interestingly, of the crimes listed in Table 1, larceny is likely the most comparable to the illegal take of wildlife. While there is a “victim” for the crime of larceny, it is a crime that is often un-witnessed and may not even be discovered by the victim for a significant period. Similarly, the illegal take of wildlife frequently goes unwitnessed and may not be discovered until much later. Furthermore, the illegal take of wildlife is often perceived as a “victimless” crime, even though it technically is the theft of public property (the trust resource).

Committing crimes is a risk-reward scenario. If a criminal perceives the reward as outweighing the risks, then the crime will likely occur. If the risks outweigh the reward, then the crime is often deterred. The three risk factors that influence the acts of criminals in the commission of a crime include: 1) Chance of detection, 2) Severity of punishment, and 3) Swiftness of punishment. Changes that result in increased detection of poaching (lowering the Dark Figure), logically should cause the rate of that crime to decrease.

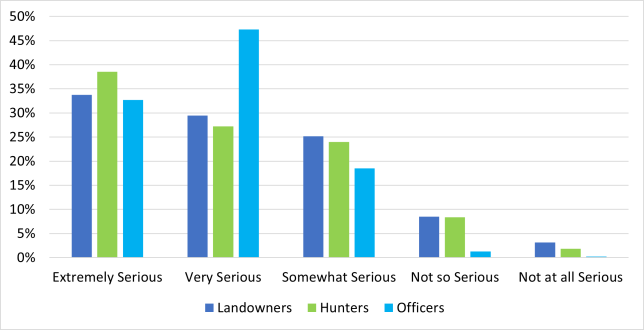

Figure 1. How serious of a problem do you consider the illegal take of wildlife to be in your state of residence in general?

In 2020, the Boone & Crockett Club, in partnership with the Wildlife Management Institute, initiated a comprehensive study of the illegal take of big game in the United States. The goals of this study are:

- A Public that clearly understands the differences in Poachers vs. Hunters.

- Significantly increased levels of detection and reporting of wildlife poaching.

- An educated hunter base, public, and judiciary on the true costs of wildlife poaching.

- Making sure the punishment fits the crime, and that punishments are administered fairly and consistently.

- Significant reductions in poaching and other wildlife crimes.

The first phase of this study was to survey persons responsible for enforcing wildlife laws (conservation officers, game wardens, etc.) as well as the persons that are most likely a witness to acts of illegal take of wildlife (landowners and hunters). In 2021, we selected eight states and conducted an extensive survey of these three groups. For Law Enforcement Officers, we administered ~1,600 surveys with a response rate of 87.5% (1,400 valid responses). For hunters, we administered 80,000 surveys with a response rate of 17% (13,675 valid responses). And for Landowners, we administered 80,000 surveys with a response rate of 5% (4,003 valid responses.

As expected, all three groups of respondents indicated that they considered the illegal take of wildlife in their state to be a serious issue, with ~88% of Landowners, ~90% of Hunters, and ~97% of Officers rating the problem as “Somewhat Serious”, “Very Serious” or “Extremely Serious” (Figure 1).

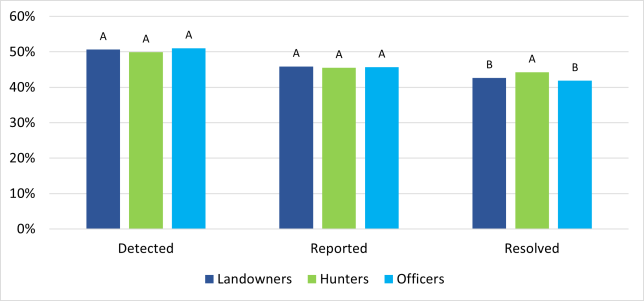

Figure 2. Indicate the percentage of illegal take that you believe goes (Undetected, Unreported, Unresolved) in your state of residence.

When asked about their opinions on the detection rate (someone other than the perpetrator knew about it), Reporting rate (Law Enforcement was made aware of it), and Resolved rate (Case was properly adjudicated in court), the three groups of respondents were uniformly consistent, with all three indicating a Detection rate of ~ 50%, and Reported rate of ~ 45%, and a Resolved rate of ~ 42% (Figure 2).

When compared to the data on the Dark Figure of person-on-person crimes in Table 1, it is apparent that even the groups most likely to encounter poaching incidents are not likely to report them. While our three survey groups indicated a Detection/Reporting/Resolve rate of around 45-50%, we suspect that this is the result of the cryptic nature of the crime. Specifically, the comparable crime of Larceny, defined as “the unlawful taking, carrying, leading, or riding away of property from the possession or constructive possession of another” has an identifiable victim who can report the crime. However, this happens in only about 18% of all cases. The more cryptic crime of poaching, where there aren’t often witnesses and where there is no identifiable victim, is likely much lower than 18% and certainly lower than the 50% reported by our survey subjects.

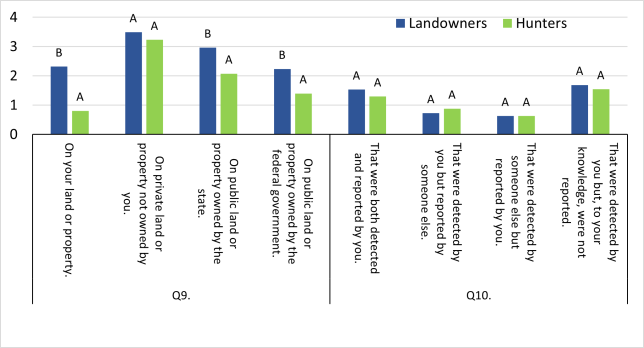

Figure 3. How many incidences of illegal take of wildlife in your state of residence are you aware of that occurred in the past 5 years?

To attempt to gauge the Detection rates of the two groups most impacted by the crime of illegal take, we asked the hunters and landowners questions about how many incidents they were aware of, where those incidents occurred, and what they did about them. Figure 3 shows that both landowner and hunter groups, on average, were aware of about two incidents per year over the past 5 years. They also indicated that these incidents occurred primarily on public lands or on private lands not owned by themselves. Finally, and most disturbingly, they indicated a reporting rate for crimes they were aware of that was substantially lower than their detection rates (Figure 3).

In summary, all three groups surveyed (Landowners, Hunters, and Officers) indicated that they consider the illegal take of big game to be a serious problem. Follow-up questions indicated that the groups felt that the illegal take of big game results in a significant negative impact to wildlife populations, hunt quality, hunt opportunity, access to hunting lands, and public perception.

Survey results also suggested that the illegal take of wildlife is cryptic, with very few incidents being witnessed even by people present on the landscape (landowners, hunters, officers) when the crimes are taking place. Although these same groups report that they feel half of all incidents are detected, reported, and resolved, data for other crimes that are studied extensively does not bear this out.

Of special concern, our survey results indicated that fewer than half that witness illegal poaching events report them to law enforcement. This indicates that the reduction of wildlife crimes by increasing reporting rates will largely need an educational approach.